David Bowie: Berlin on His Skin

Between shadows, canvases and songs, the city that broke him and then remade him.

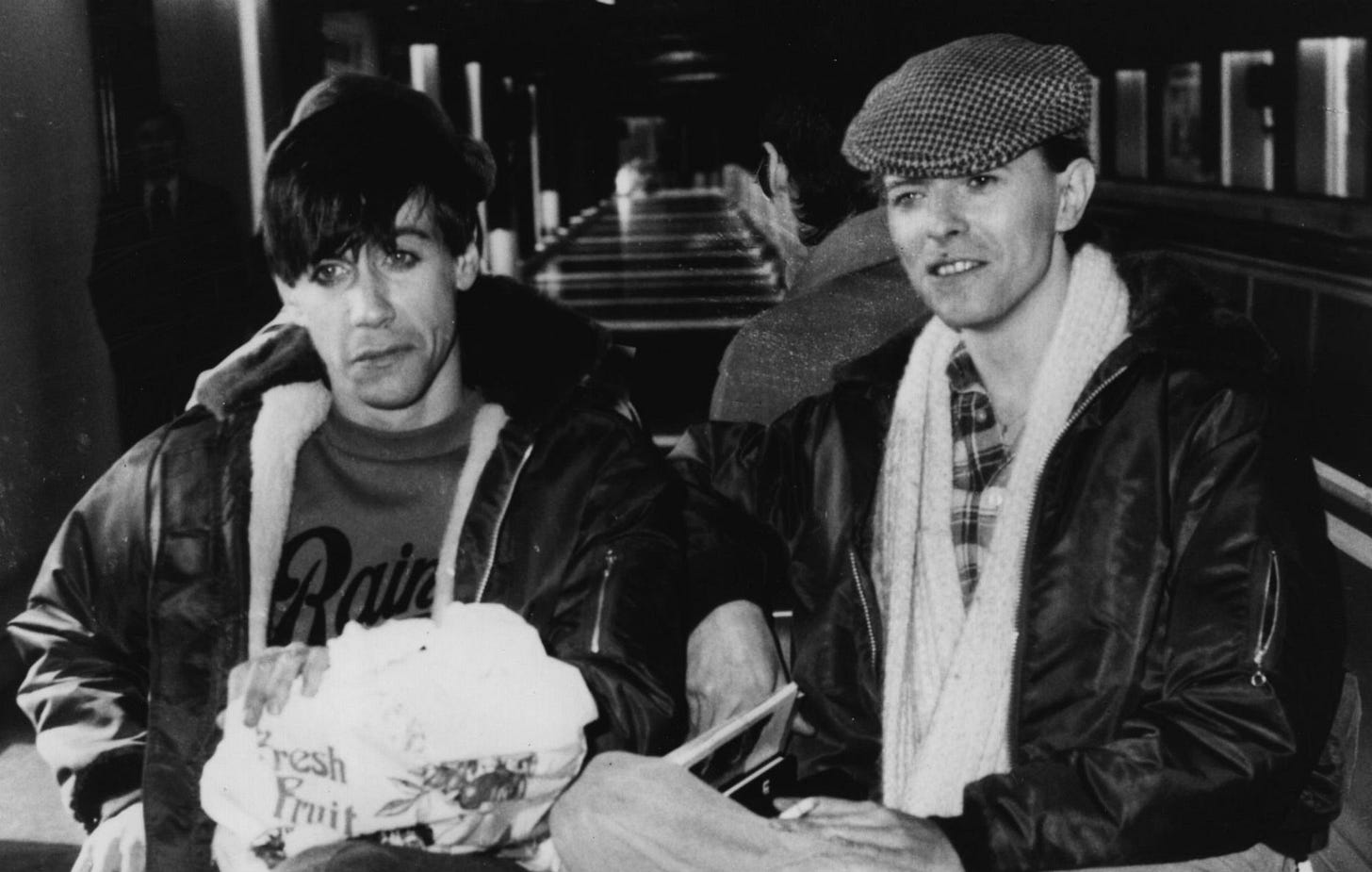

When David Bowie and Iggy Pop arrived in Berlin at the end of the 1970s, the city welcomed them with its divided face: on one side the West, with the smoky clubs of Kreuzberg, the neon of the Kurfürstendamm and the restless nights of underground theatres; on the other side the East, grey and militarized, sealed behind the Wall. A fragile island in Cold War Europe, a place breathing both capitalism and decay, suffocated in its own alienation. In that atmosphere of precarious contrasts, artists, drifters, students and visionaries found – and lost – themselves.

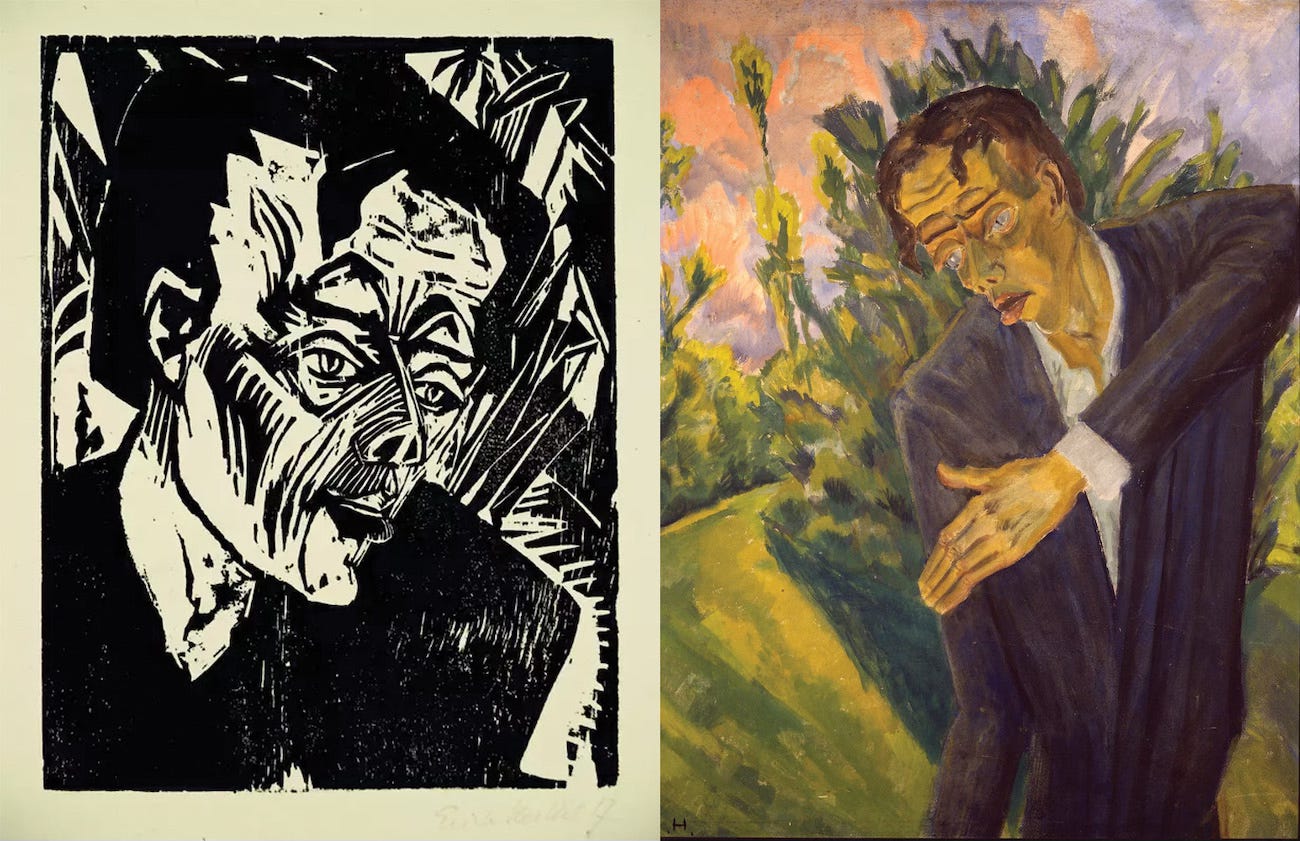

Berlin had already been like this in the Weimar Republic of the 1920s: a crucible of freedom and experiment that had spawned scandalous bohemian haunts, avant-garde theatres, Expressionist art and cinema, the wild nights of Anita Berber and Kirchner’s canvases. Then came Nazism, the war and finally the Wall, yet the city never stopped transforming. In the 1970s, scarred and divided, it still devoured nights, loves and anxieties – dazzling precisely in its awareness of being ephemeral.

With Bowie’s arrival, both the artist and the city entered a new season of cultural bloom, rekindling that flame and turning Berlin into a canvas of sound and vision.

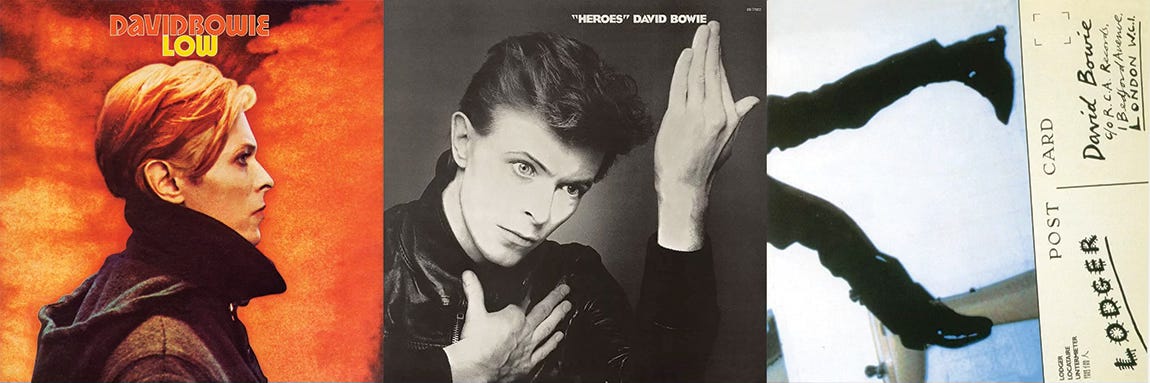

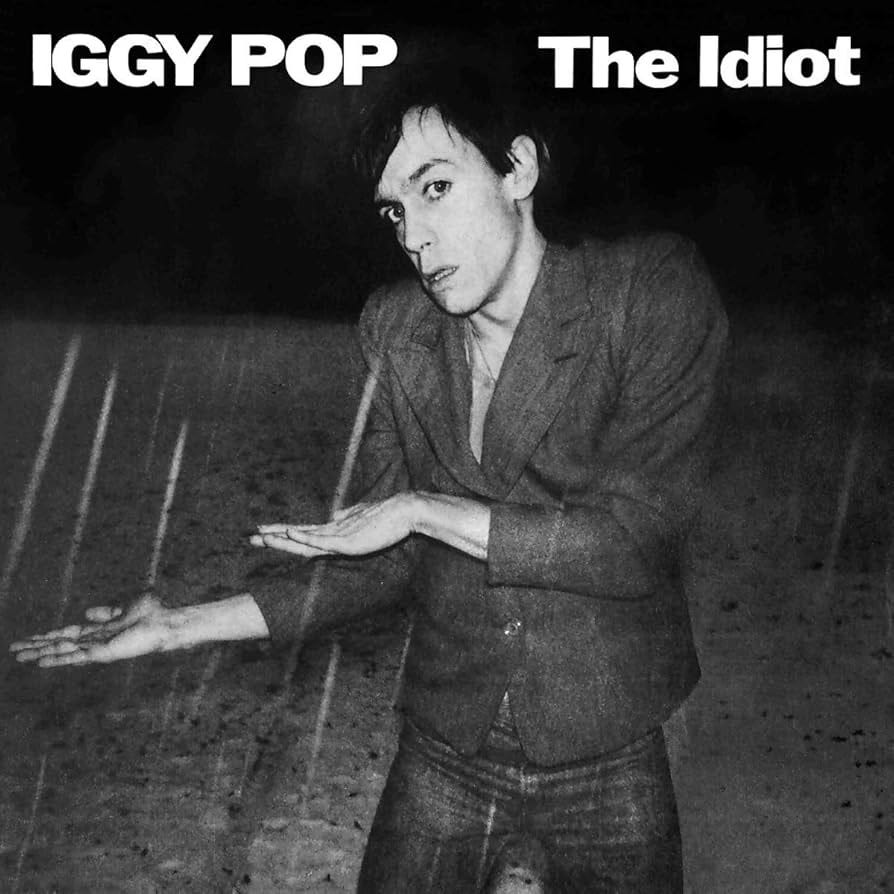

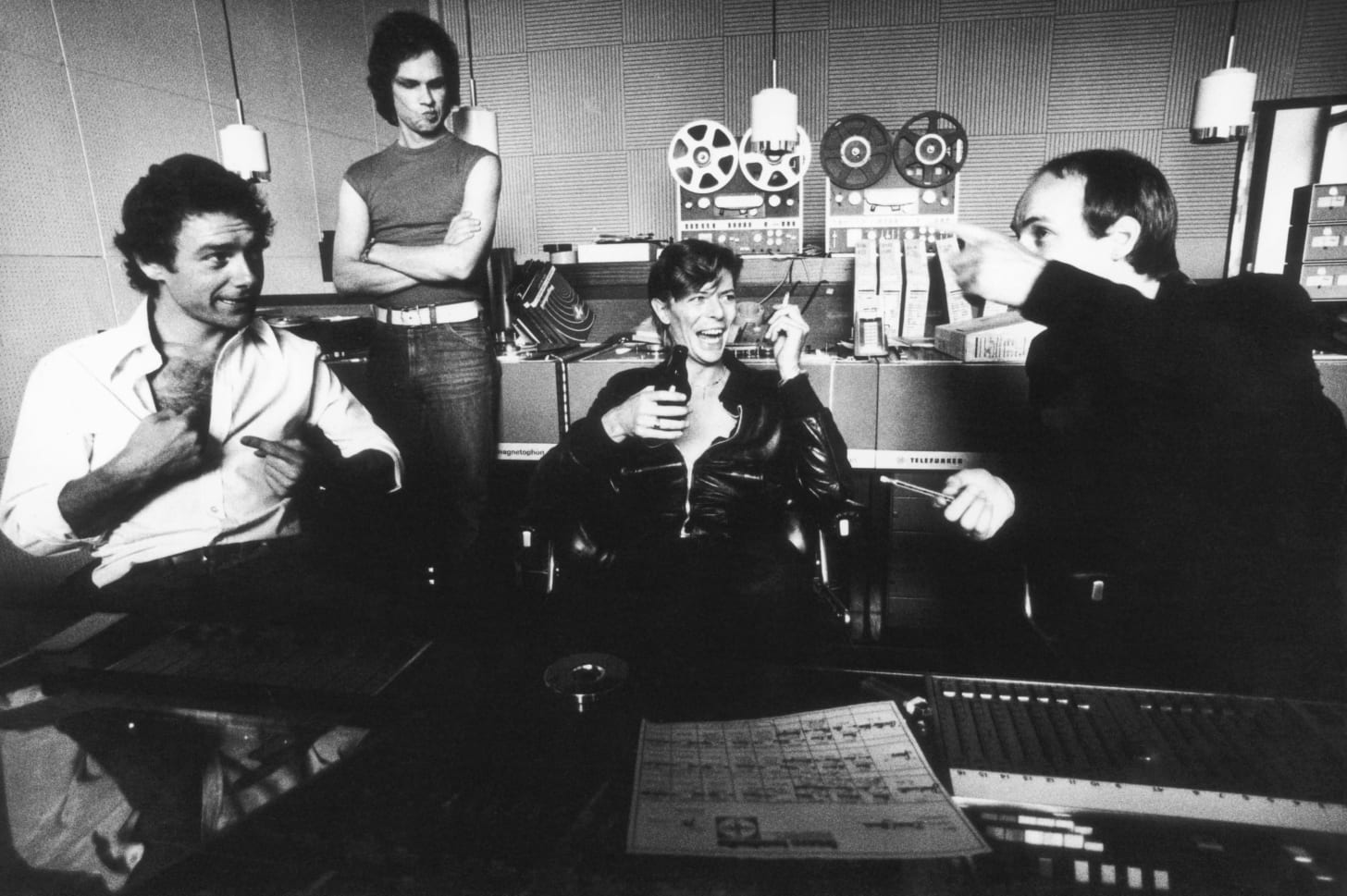

From that radical, cosmopolitan season came five albums: Bowie’s Berlin trilogy – Low and Heroes (1977), Lodger (1979) – and for Iggy Pop, The Idiot and Lust for Life (1977). Bowie, exhausted by the cocaine spiral and fame that had devoured him in Los Angeles, sought escape, a clean break from the characters that had made him an icon but now seemed “hollow”. Iggy was in no better shape. West Germany appeared as a refuge, and Berlin as the exact place to start again.

At Bowie’s side was Brian Eno, a visionary mind and silent accomplice. Not a producer in the strict sense, but a catalyst of possibilities: with his Oblique Strategies — cards filled with aphorisms and perspective-shifting provocations — he pushed Bowie to attempt paths he might never have taken alone. The rarefied atmospheres of Low, the soundscapes of Warszawa and Neuköln, the electronic hypnosis of Heroes owed much to that alchemy: Bowie was searching for a new skin, and Eno offered him a laboratory of sounds he had absorbed from German Krautrock, from Kraftwerk to Cluster. Together they turned divided Berlin into a blueprint of the future.

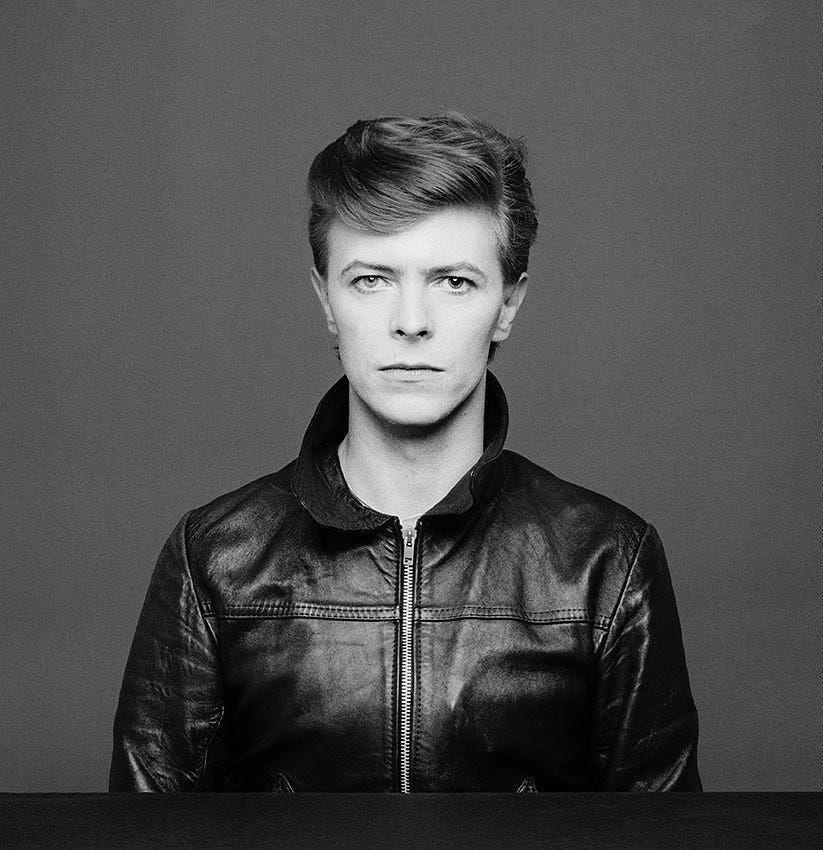

Yet beyond the sounds and the strategies, there was the man. Bowie arrived worn out from Los Angeles, exhausted by himself, by cocaine, by characters he could no longer sustain. Years later he would put it plainly: “Life in LA had left me with an overwhelming sense of foreboding. I had approached the brink of drug-induced calamity one too many times and it was essential to take some kind of positive action. For many years Berlin had appealed to me as a sort of sanctuary-like situation. It was one of the few cities where I could move around in virtual anonymity. I was going broke; it was cheap to live. For some reason, Berliners just didn’t care. Well, not about an English rock singer anyway.”

Bowie chose to live in Schöneberg, the district that had seen the births of Marlene Dietrich and Blixa Bargeld. He even dedicated a track, Neuköln, to another Berlin neighbourhood. Berlin was not Paris with its romance, nor London with its eccentricity: it was a concrete jungle populated by eccentrics and visionaries, heir to the Expressionists and marked by a keen sense of its own transience.

That condition ran through both the city and Bowie’s music. Heroes is not just an album, but the sonic portrait of a city and its lovers kissing by the Wall. Low and Lodger carry the same sense of alienation and modernity that one breathed in Alexanderplatz or Bahnhof Zoo, amid crossing trams and drab buildings that seemed torn from a Kirchner painting.

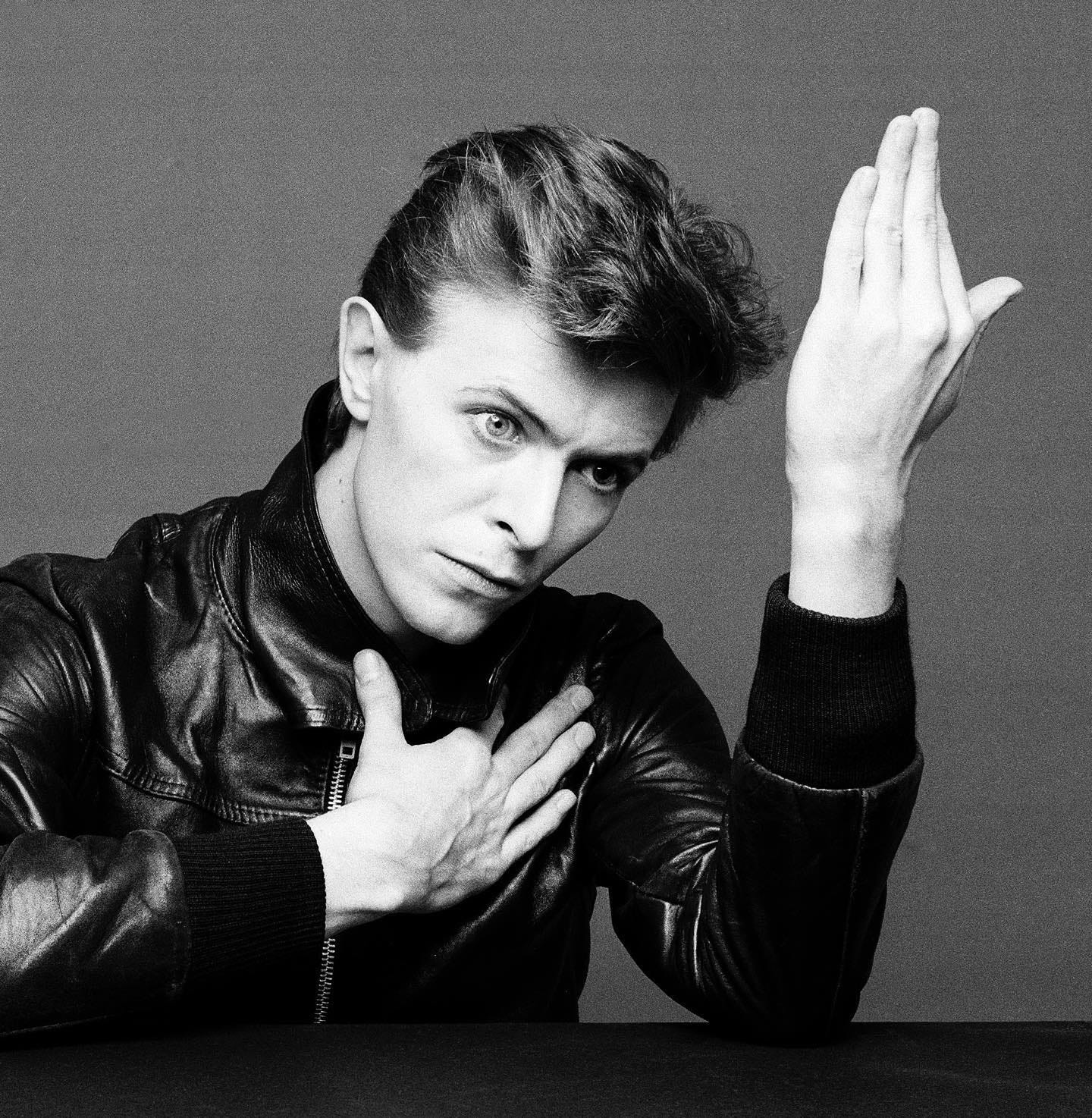

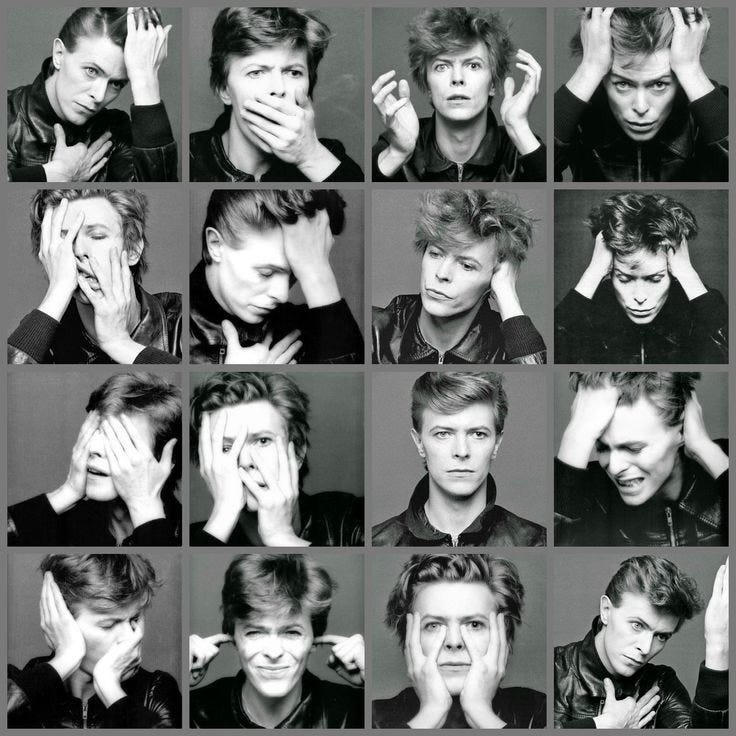

Bowie’s fascination with German Expressionism did not spring up overnight. As a teenager, still David Robert Jones at the Beckenham Technical School in Bromley, he studied art and design under Owen Frampton – Peter Frampton’s father – whom he would later remember as “an excellent art teacher and an inspiration”. From then on, he chased jagged lines and tormented figures: Erich Heckel’s woodcuts, Kirchner’s acid faces, the distorted sets of films like Wiene’s Cabinet of Dr. Caligari or Murnau’s Nosferatu. Images that already seemed like music, made of edges and shadows, of raw emotion without the need for plot. Small wonder those visions resurfaced in Sukita’s shots for Heroes, in the violent reds of Bowie’s Berlin paintings and in the soundscapes of Low.

In Berlin he frequented the newly opened Brücke Museum. “Since my teenage years I had obsessed on the angst-ridden work of the Expressionists, painters and filmmakers, and Berlin was their spiritual home. It was an art that mirrored life not by event but by mood. This was where I felt my work was going,” he told Uncut in 1999.

Above all, one painting struck him: Roquairol (1917) by Erich Heckel, a portrait of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner in nervous collapse. He didn’t just admire it: he reinterpreted it. First convincing Iggy Pop to pose in the same attitude for the cover of The Idiot. Then transforming its echo into Masayoshi Sukita’s photograph that became the cover of Heroes. Those rigid hands, that feverish gaze: a photograph that was already painting, an icon beyond time.

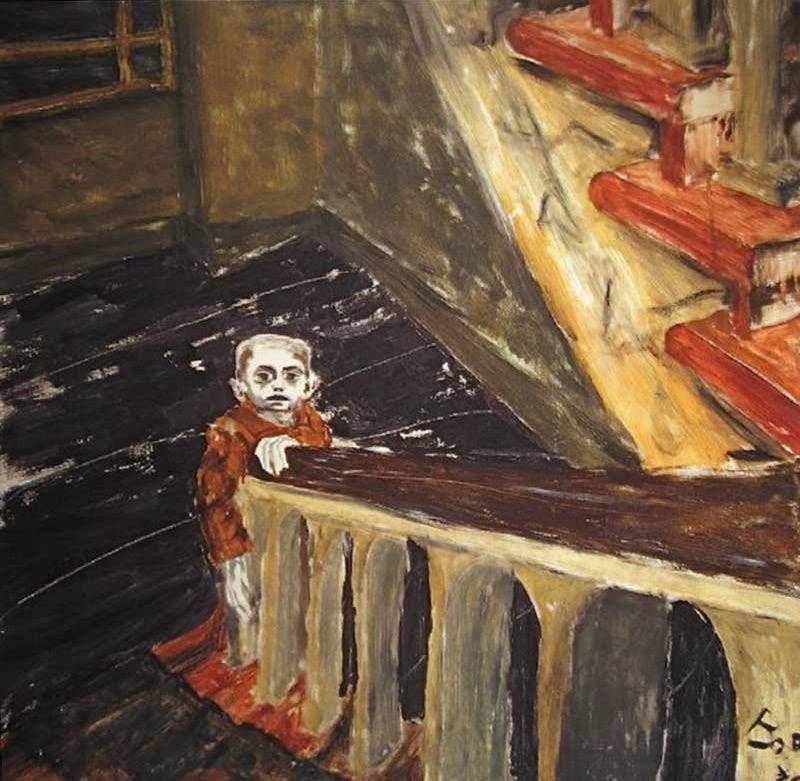

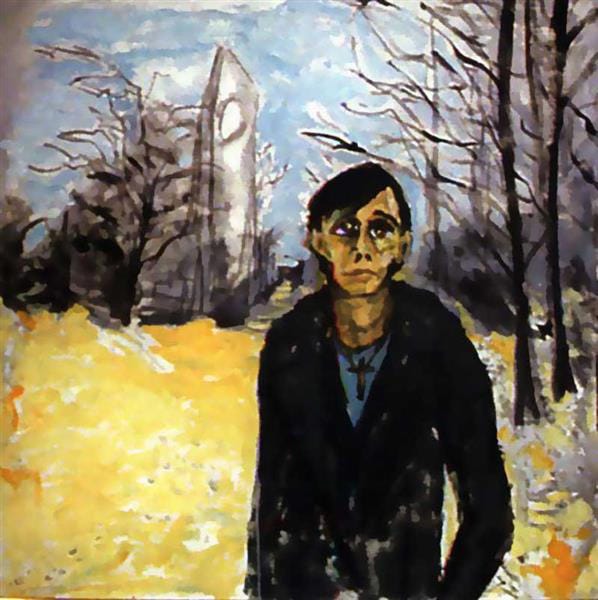

Meanwhile, Bowie painted. His canvases from those years – Child in Berlin, Berlin Landscape with JO – carry the same urgency as his records. Bold colours, distorted figures, unsettling self-portraits, urban landscapes steeped in unease. Expressionism filtered through a soul searching for salvation.

He never stopped painting. In the 1990s he produced portraits of Yukio Mishima, the Japanese writer he admired for his tragic aesthetics and obsession with beauty and death. He developed the DHead series, dozens of oil and acrylic portraits, often of friends and collaborators like Mike Garson: sharp-edged, exaggerated visages that looked like Expressionist caricatures of a personal gallery of ghosts. From travels with Iman in South Africa he drew inspiration for works linked to the “white ancestor” myths of local tribes: totemic faces and figures, drenched in bold colours, fusing African influences and European Neo-Expressionism.

It was parallel work, carried out in stolen hours, away from the spotlight of tours and studios, yet with the same urgency. A private laboratory, a visual diary of his life, where his literary interests, his journeys, his relationships surfaced on canvas.

He exhibited rarely – in London and Basel in the mid-1990s – and let his records speak louder than his paintings. But painting was part of the same creative flow. “If I want to paint or do installations, I’ll do it,” he told the Telegraph in 1996.

Music and painting were two dialects of the same language. In his canvases one can feel the same energy that runs through Sound and Vision or Sense of Doubt. Looking at his self-portraits, one recognises the same restlessness that vibrates in Blackstar. Bowie turned city, art, and pain into new forms.

Berlin welcomed him with anonymity, freedom, fertile ground for experiment. In return Bowie gave it three albums he defined as “my DNA”, etched into sound and collective imagination like few others. In those streets he learned he no longer needed masks; he could step onto the stage simply as David Bowie.

And yet his Berlin season was more than a transitional chapter: it was survival, a creative workshop that would shape everything that followed. From the minimal synths of Low to the urban distortions of Heroes, from the blood-soaked canvases to the DHead portraits, every creation bore the imprint of the divided city and its Expressionist gaze.

Many years later, when the world believed him retired, Bowie returned quietly with a single released without warning on 8 January 2013, his sixty-sixth birthday. Where Are We Now? was a fragile ballad, almost a whisper, that brought Berlin back to the surface: Potsdamer Platz, KaDeWe, the Bösebrücke that opened the night of 9 November 1989. No characters, no masks: just Bowie, his voice aged by time, singing of the city that had saved and changed him.

The video directed by Tony Oursler deepened this sense of memory: Bowie and artist Jacqueline Humphries — abstract painter, chosen because she resembled Corinne “Coco” Schwab, his loyal assistant in the Berlin years — appeared as two puppets with projected faces, seated on a suitcase. Behind them rolled black-and-white footage of divided Berlin: the Victory Column, the Reichstag, Alexanderplatz, the overpasses of Potsdamer Platz. In the studio, a chaos of symbols: mannequins, bottles, a diamond, a giant blue ear, an empty frame — relics of a private memory merging with the city itself.

Even personal wounds resurfaced: the T-shirt reading Song of Norway, recalling the film in which his former girlfriend Hermione Farthingale appeared after leaving him in 1969. As if Bowie wanted to braid his most intimate scars with his Berlin memories.

Where Are We Now? was greeted as a moving and unexpected return. But it was more than that: proof that Berlin had never been just a creative parenthesis, but the secret compass that guided his life and art to the very end.

More than ten years after his death, that Berlin chapter remains a turning point not only in his career but in the history of contemporary music. Berlin gave him refuge and anonymity; he repaid it with works that still tell of the courage to reinvent oneself. That is why Heroes is not just a record: it is proof that art can keep you alive, that a wall can become a stage for freedom, that even chaos can be transformed into immortal beauty.