Dead Man: The Electric Breath of Dusk

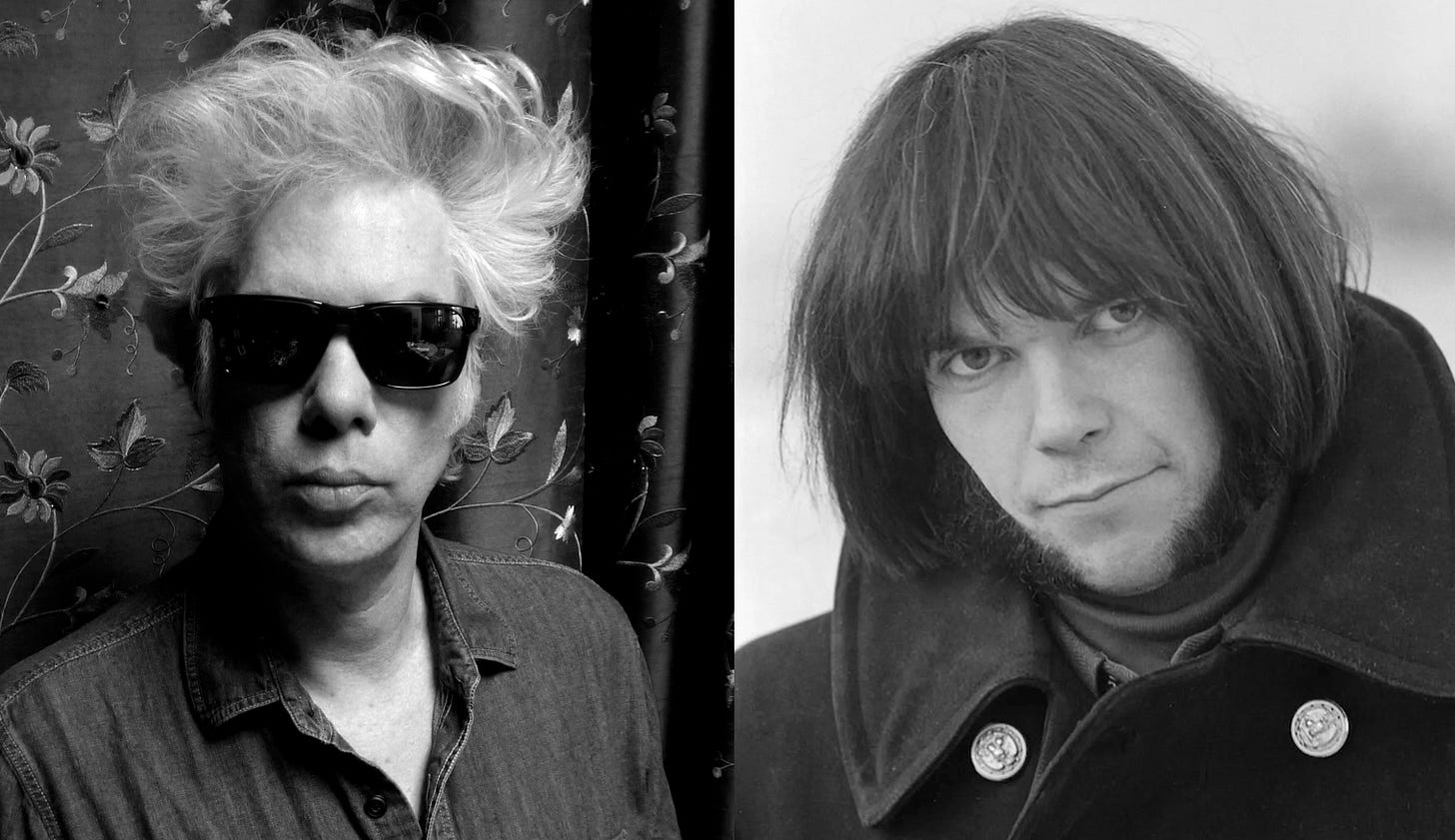

Neil Young and Jim Jarmusch make the Western sing its own requiem.

There’s a Jim Jarmusch film that opens on the rails of the West and closes like a fever dream — cracked, smoky, and beautiful. Dead Man (1995) is a movie you don’t simply watch; it’s a landscape you have to cross, step by step, through grit, gunfire, and hallucinations.

From a train carriage thick with smoke and silence begins the journey of William Blake — an unarmed, aimless accountant — who meets Nobody, a native without a tribe, his mirror and compass. Together they move toward the darkness, two shadows that no longer belong to the living.

Instead of solemn choirs and galloping strings, the soundtrack belongs to Neil Young and his battered Old Black guitar, crackling like a live wire. No themes tu hum, no comforting melodies — just electric improvisations, chords fading into the void, sounds leaking in from some other dimension.

The result is a film where sound and image don’t meet halfway — they melt together. Dead Man becomes a black ballad in which the music doesn’t accompany the characters; it stalks them, whispers to them, reminds them that their fate was written long before they set foot on screen.

A Broken Dream of the Frontier

Anyone expecting John Ford’s West — heroic silhouettes and horses vanishing into the sunset — will be disappointed. Jarmusch flips the genre inside out: no heroes, no glory, just a lost accountant swallowed by a hostile world.

Machine, the town of smoke and gears, is proof enough. It’s an industrial hell that reeks of coal and rust, more Charles Dickens than Sergio Leone. Robby Müller’s milky black-and-white turns the landscape into a living daguerreotype: prairies and forests that aren’t promises of freedom but warped, ghostly corridors. There’s no nostalgia here — only disorientation.

Machine isn’t just a factory town; it’s a Kafka trap, a senseless mechanism grinding down whoever walks in. Watching it, you think of Terry Gilliam’s Brazil — the same absurd machinery, the same corridors that lead nowhere. Blake isn’t doomed because he’s weak, but because the system itself is meaningless.

Dead Man belongs to that strange bloodline of the acid western — the bastard child of the spaghetti kind. It takes the wide plains and lonely journeys of the West, stirs in existential dread, surrealism, and black comedy, and ends up with something that looks like nothing else. A western that stares at itself after a sleepless night and laughs through its cracked teeth.

Here Jarmusch tears down the myth of Manifest Destiny. His West isn’t a dream being built — it’s already collapsing, eaten alive by greed and violence. Religion, far from redemption, is just another brand of rot: missionaries spreading disease, industrialists waving holy icons as excuses. Expansion is just another word for consumption.

The Gaze of the Dead Man

In casting Johnny Depp, Jarmusch didn’t want a gunslinger but a face too soft to survive the frontier. His William Blake moves like an outsider — dressed in black among men caked in dust, polite among killers, perpetually out of place.

Depp’s performance lives in silence: wide eyes, hesitant steps, gestures that never find their ground. He’s not a cowboy — he’s an intruder. And that’s why Neil Young’s music fits so perfectly. Those buzzing strings and hanging notes seem to breathe with Blake, translating the anxiety he can’t express.

The first truth comes from Thel, a paper-flower seller with a pistol under her pillow. “Why do you keep it?” Blake asks. “Because this is America,” she says — a line as sharp as a gunshot, summarizing the entire nightmare.

As the film goes on, Blake sheds his skin. The mild accountant turns, almost by accident, into an avenging angel, leaving behind bodies and blood. Yet he never stops looking surprised at his own violence. Depp holds the contradiction together — victim and executioner, absurd and tragic, an unwitting poet writing his work in blood.

And in Nobody — the outcast native, twice rejected, once by the whites and once by his own — he finds his mirror. Two nameless men who share one last direction: forward, into the dark.

The Guitar as Revelation

Jarmusch didn’t hand Neil Young a script or a score. He just said, Watch the film. Play what you feel.

What began as a chance meeting — a Crazy Horse concert near the shooting location — turned into an unrepeatable collaboration. Young briefly thought of bringing in Krist Novoselic and Dave Grohl from Nirvana, but eventually decided to stay alone: This is one man’s journey. It needs one guitar.

So, in a San Francisco warehouse mic’d up like a cave, Young watched a rough cut of the film three times and played live. His Old Black spat jagged bursts, low drones, chords dying like embers. Sometimes percussive, sometimes mournful, always raw — raw as a skinned beaver left in the sun.

It’s less a soundtrack than a weather system — drifting in, crackling, eroding everything in its path. It’s something ancient and modern at once — the sound of the American machine colliding with the mysticism of Nobody. If Ennio Morricone filled the desert with brass, Neil Young tunnels into Blake’s skull: riffs looping and mutating, circling like vultures over a dying body.

The film’s main theme, curiously, never made it to the official soundtrack. The album itself is a ghostly artifact — seven improvisations stitched with dialogue, ambient hums, and Johnny Depp reading the real William Blake. Half record, half séance.

At its heart lies Guitar Solo No. 5 — fourteen minutes of wounded chords, feedback explosions, and sighs turning into landscape. It’s not accompaniment; it’s initiation. A guide leading the viewer into Blake’s own vision quest.

Young’s guitar doesn’t follow the images — it seeps through them like groundwater. Every string vibrates where the frame cracks; every silence leaves a wound. The score breathes with the film, sharing its pulse and its exhaustion. Like Blake himself, it walks toward the end — dying, note by note.

Bodies, Strings, and Dust

Where the old West galloped in rhythm and rhyme, Dead Man limps along on a wounded riff. Neil Young paints Blake’s fractured consciousness in sound — the whisper that there’s no way back.

Other filmmakers would later use sound as rupture: Jonny Greenwood in There Will Be Blood and The Master, his strings flaring like nerves; Mica Levi in Under the Skin, turning alien touch into magnetic distortion; Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross in The Social Network, making electronic hum the heartbeat of self-consuming power. But none sound as primal, as alive, as haunted as Neil Young alone in that warehouse of amplifiers and ghosts.

And then there’s the chorus of outsiders. Just look at the faces drifting through Dead Man: Crispin Glover, Iggy Pop in a bonnet, Billy Bob Thornton, Jared Harris, Lance Henriksen, Robert Mitchum, John Hurt. A traveling freak show of lost souls, every one of them an apparition from some other world. It’s a frontier with no center — just a constellation of shadows.

Even the real William Blake entered the film by accident. Jarmusch, exhausted from research into Native traditions, picked up the poet’s work and found a perfect echo — the same visions, the same feverish mysticism. That coincidence turned an accountant into a metaphysical pilgrim, a name into a prophecy.

In the end, Dead Man lingers like a piece of skin left to dry under the desert sun — cracking, curling, eroding in a wind that never stops blowing. That’s its secret: a film you don’t just watch but wear, like a slow, merciless song that stays on your skin long after the screen fades to black.