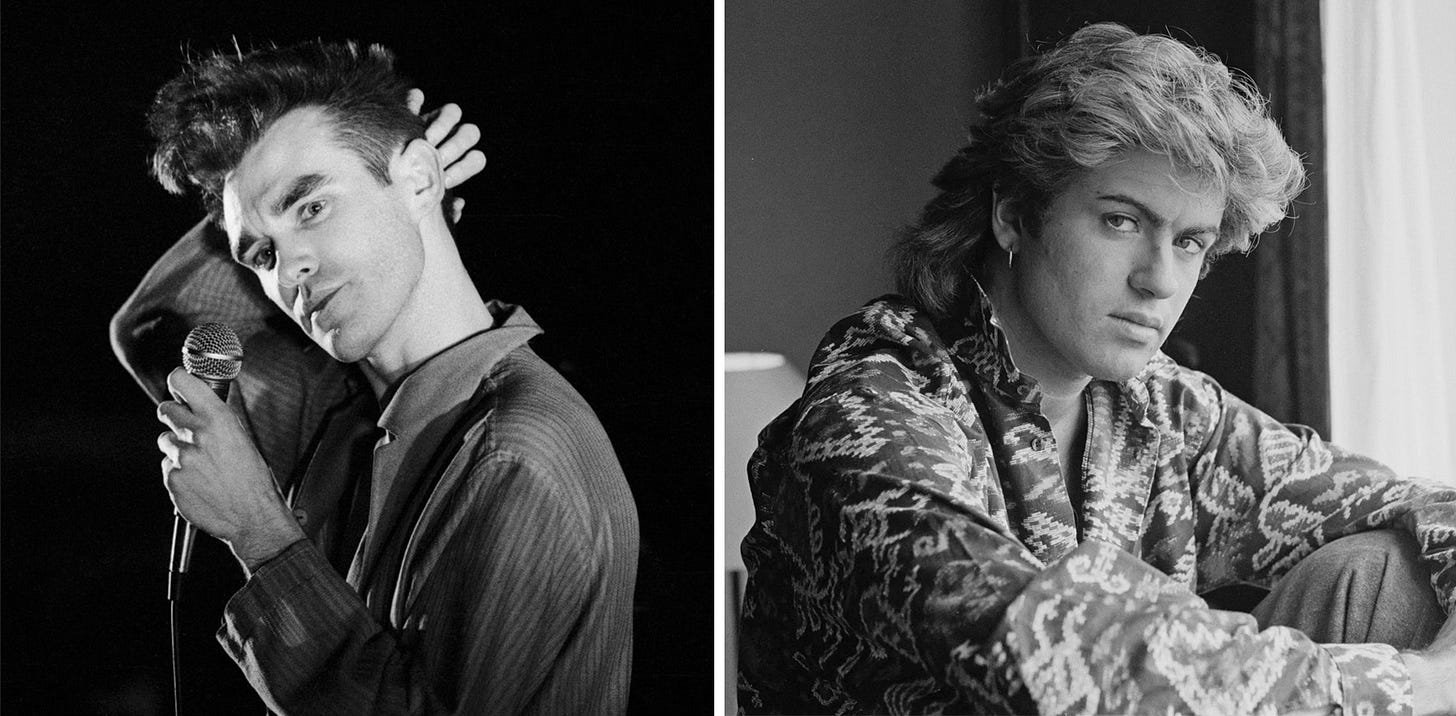

George Michael vs Morrissey: Clash Over Joy Division

Amid the glitter of the ’80s, between synth-pop and neon lights, George Michael stunned everyone by praising the darkness of Joy Division—while Morrissey shrugged them off with icy disdain.

There’s an image we all carry when we think of the 1980s: neon everywhere, jackets with shoulders as wide as highways, oceans of hairspray, and choreographed dance routines on MTV. And right in the middle of that glitter storm was George Michael, smiling from every bedroom wall, singing with Wham! about Club Tropicana and carefree holidays.

But behind the pastel colors and sun-soaked hits, there was a man who took music seriously. Someone who listened carefully, who felt deeply, who knew the difference between surface sparkle and true beauty.

That’s why a forgotten BBC broadcast in 1984—Eight Days a Week—has become a cult moment for music lovers. The premise was bizarre: sit George Michael, Morrissey (then frontman of The Smiths), and veteran pop DJ Tony Blackburn on a couch, hand them Mark Johnson’s Joy Division biography An Ideal for Living, and see what happens. Spoiler: it didn’t go as expected.

First up was Morrissey, the man everyone assumed would be Ian Curtis’ kindred spirit. Instead, in his typical aloof tone, he dismissed the band with a shrug. He spoke about the obsession with Curtis’ death, about the sadness of it all—but musically, he said he felt “nothing whatsoever” for Joy Division. A cold rejection, especially from the patron saint of melancholy.

Then came Tony Blackburn. The radio DJ with a permanent grin, forever associated with the glossiest side of pop. He admitted he was “more of a soul man,” then trashed the book as “boring” and “disturbing,” adding—astonishingly—that it didn’t focus enough on Curtis’ suicide. Live on BBC primetime. A true “did-he-really-just-say-that?” moment.

And then, salvation. George Michael.

Host Robin Denselow turned to him, half-smiling: “George, I wouldn’t have imagined you as a Joy Division fan…”

George leaned back, flashed his knowing grin, and replied:

“You might be wrong.”

What followed was a surprise for everyone in the studio. George admitted he found the book pretentious—but then delivered a heartfelt defense of the band. He confessed that he loved their music, that the second side of Closer was “beautiful” and “one of my favorite pieces of music.” He praised the fact that the book wasn’t just another obsessive rehash of Curtis’ death but actually tried to capture the music itself.

Just as George was getting into his flow, making the case with sincerity and warmth, the segment was cut short. TV time waits for no one. But the damage—or rather, the magic—was done.

Looking back, the moment feels prophetic. George Michael would later be hounded relentlessly by tabloids, mocked and exposed for his private life, forced to endure a level of public scrutiny that would have broken many. And yet, in 1984, with the whole world expecting a shallow pop idol, he revealed himself as a listener of rare empathy—someone who could find beauty in the darkness of Joy Division.

That night, George Michael proved he wasn’t just the smiling king of pop hits. Beneath the white shirts and golden tan, there was a man who understood melancholy, who recognized greatness even in music born of despair.

And in that small corner of BBC history, George Michael did what few expected: he gave Joy Division the respect they deserved—while Morrissey, of all people, turned his back.