When an Angel fell on a Nick Cave Song

How "Wings of Desire" turned a divided city into poetry and found in Cave’s voice its living flesh

Wings of Desire is not a film that can be summed up in a few lines: it is a suspended parable, a poetic diary disguised as cinema. In 1987, Wim Wenders returned to his city, still divided by the Wall, and imagined two angels — Damiel (Bruno Ganz) and Cassiel (Otto Sander) — walking invisibly among the people of Berlin. They listen to thoughts, collect confessions, witness lives broken by solitude and haunted by war. Only children can see them, because only children still have eyes pure enough to glimpse the invisible. But when Damiel meets Marion (Solveig Dommartin), a melancholy trapeze artist with stage wings costume and a wavering heart, he realizes that watching is no longer enough: he wants to touch, to love, to fall.

The film drifts in a milky black and white that, at times, opens into color — as if human experience itself were a sudden explosion inside a dream. It is made of inner monologues written by Peter Handke, of gazes resting on ruins and deserted squares, of music that swings between the celestial rarefaction of Jürgen Knieper and the earthy ferocity of Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds. It is not merely a love story: it is a portrait of Berlin in its melancholy and resilience, a visual poem that in 1987 won Wenders the Best Director award at Cannes.

Berlin: a wound that breathes

When Wings of Desire was released, the Wall still stood — massive, stubborn, dividing the city like a scar that refused to heal. Returning after years abroad, Wenders found not just a wounded Berlin, but a city breathing his same solitude: squares emptied of traffic and trust, train stations reduced to shells, buildings in ruins standing as silent guardians of a faded glory. The sky was low, gray, and every corner sounded like a broken music box.

West Berlin was a peninsula suspended in time — physically isolated, yet strangely alive: neon lights flickering in the mud of the streets, clubs like Risiko and Dschungel where punks, new wavers, skinheads, artists and outsiders tried to build a community in the shadow of the Cold War. Photographers captured scribbled walls, rebellious faces, noisy ideas, while on the other side the GDR stared back with grim detachment.

With the eyes of an exile and a poet, Wenders saw that this cruelty of architecture, those abandoned spaces, those ruins were not only rubble but memory. They echoed the past of the Second World War, devastation and loss, but also the fragile hope of small artistic communities trying to reinvent the city. Out of that suspension came the idea of the angels: silent, invisible figures perched on statues like the Siegessäule, wandering through the shelves of the Staatsbibliothek, lingering in the ruins of Anhalter Bahnhof. Not saints, but poetic projections — visions born from the verses of Rainer Maria Rilke, the canvases of Paul Klee, conversations with Peter Handke. Creatures condemned to observe without touching, who walk along the thresholds between light and shadow, past and present, in a city still living inside its open wound.

Angels and the music of silence

Through Henri Alekan’s lens, Berlin becomes a suspended, opaque black and white, where every ray of light seems to hold its breath before falling on the ruins. Streets and buildings turn into fragile silhouettes, as if the city itself were a dream balanced on the edge of collapse. Jürgen Knieper’s score sustains that suspension: harps like drops of water, synthetic choirs floating in the air, a cello crying with a human voice, embodying the melancholy of Damiel the angel.

The thoughts of Berliners — fragmented, contradictory, mundane — weave into this sonic fabric like invisible threads: whispered confessions between library shelves, solitude surfacing on trams, half-spoken desires in bars still empty at dawn. It was the music of a suspended, wounded world, struggling to breathe. And when the story bends toward flesh, toward the fall, Wenders summons the most earthly, nocturnal and lacerated voice Berlin could offer in those years: Nick Cave.

The fracture: Nick Cave and the city’s heart

Back in her trailer after the trapeze act, Marion lowers the needle onto a record. The suspension cracks. From the hiss of the grooves emerges The Carny, from the album Your Funeral… My Trial (1986). A crooked, macabre, magnetic waltz that tells of a vanished circus performer and leaves behind a trail of unease and mourning. Marion listens intently, sometimes humming along, as if seeking comfort in that dissonance: in its dark lament she recognizes her own solitude. And Damiel, invisible beside her, hears the call. For him — who until then could only observe and record — the music becomes the first door left ajar onto the mortal world, a sudden breach revealing the vertigo of feeling.

In that instant, an invisible triad forms: Marion is the body of the world, fragile and earthly; Damiel, watching without touching, is the soul of the world; and Nick Cave, voice crackling from a scratched record, becomes the intellect of the world, singing universal stories of abandonment and crumbling circuses. The Carny ceases to be just a song: it becomes both mirror of Marion’s condition and threshold that tempts Damiel toward the fall.

But it is in the red, smoky belly of a Berlin club that the fracture rips wide open. On stage, Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds launch into From Her to Eternity, the title track of their 1984 debut. Cave’s voice writhes like a fever dream, telling of a man obsessed with the woman upstairs — desiring and fearing her, until love turns into threat. It is a song of desire as abyss, of closeness and distance devouring one another, of passion that offers no escape. Within the film, that performance is not a mere interlude: it becomes the very soundtrack of the fall. While Cave howls his torment before a spellbound crowd, Damiel chooses to renounce eternity and embrace the fire that music has shown him without mercy.

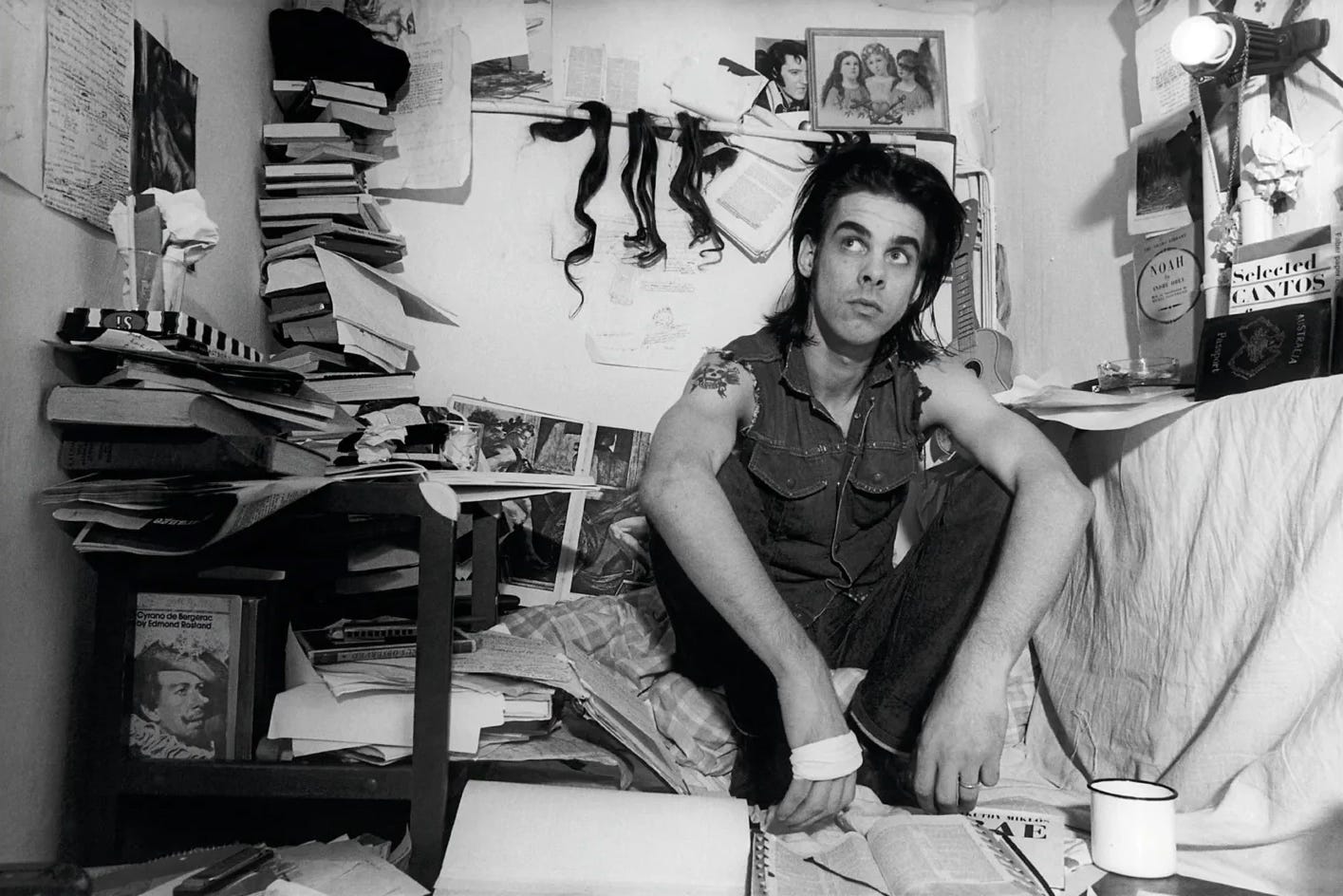

Nick Cave between heaven and earth

He was not just a musician in the background: in Wenders’ film, Nick Cave becomes a threshold. His songs are the fissure through which the world of senses, desire, chaos floods in. Alongside the vigilant silence of the angels, his voice embodies another form of secular sacredness: a nocturnal prophet singing obsession, loss, love turning to menace. Wenders himself admitted it: to make a film in Berlin without Nick Cave would have been a sin of omission.

The Carny, recorded in Berlin at the Hansa Studios that had welcomed David Bowie and U2, tells of a circus collapsing, horses abandoned, communities dissolving. It is not just the track Marion puts on the turntable: it is a self-portrait of the city itself, marginal and nomadic, in mourning and transformation. And then From Her to Eternity — a scream of carnal obsession that within the film becomes a narrative catalyst: it is while Cave bellows it on stage that Damiel chooses to fall, to become a man, to finally share the same plane of existence as Marion.

The fall and the inevitable encounter

It is the moment when everything changes — for the story and for the audience. The angel falls and becomes man: suddenly the world ignites in color, and every simple gesture — blood pulsing in his veins, the bitterness of coffee, the sting of a first cigarette — appears as a daily miracle. The camera lingers on them as if on revelations, fragments of a life that until a moment before had been denied.

Guiding him through this earthly baptism is not only Marion, but also an unexpected presence: Peter Falk (playing himself), whom the film reveals to be a former angel. With the disarming warmth of a smile, the actor audiences knew as Columbo becomes a terrestrial Virgil, teaching Damiel the joy of small things, the beauty of holding in one’s hands what can finally be touched. Marion — the trapeze artist who had sensed his presence without ever seeing him — now recognizes him in the stranger who approaches her at the bar. They embrace, while the roar of the Bad Seeds fades and a string quartet enfolds the scene. For a moment, the sky over Berlin bends low enough to brush the earth.

It is no wonder that, after this appearance, Cave began to modulate his writing differently, allowing tenderness and fragility to live beside fury and darkness. In that encounter, cinema and music do not merely cross paths: they fertilize one another, transforming into something that no longer belongs entirely to either.

In that red, smoky club, Nick Cave does not accompany the story: he makes it inevitable.